New America Foundation, American Strategy Program, Global Governance Initiative.

Parag Khanna directed the Global Governance Initiative. He is also a Senior Research Fellow at New America. Global Governance Content up to 2008.

New America Foundation

Launched in 1999, the foundation was guided through a period of rapid growth by founding president Ted Halstead. The institute is now led by President and CEO Steve Coll and an outstanding Board of Directors, chaired by Eric Schmidt. New America is headquartered in Washington D.C. and also has a significant presence in California, the nation’s largest laboratory of democracy.

New America’s Leadership Council, chaired by John C. Whitehead. Whitehead was also the Chairman of the Goldman Sachs Foundation.

John J. Weinberg Obituary, 2006

All the names are noteworthy but these names are particularly so:

Susan Chambers, Wal-Mart

Jeffrey Leonard, President & CEO, Global Environmental Fund

Lenny Mendonca, McKinsey Global Institute

Eric Schmidt, Chairman & CEO, Google, Inc. Chairman-elect, New America Foundation Board

Bernard L. Schwartz, retired Chairman & CEO of Loral Systems & Communications, Inc.

Harry Sloan, Chairman & CEO, MGM, Inc.

Jonathan Soros, President and Co-Deputy Chairman, Soros Fund Management, Inc.

Board of Directors – take note of the names

Born in India – grew up in Saudi Arabia

Born in India – grew up in Saudi Arabia

Parag Khanna, Director of the Global Governance Initiative, New America Foundation; Bernard Schwartz Research Fellow

I believe we focus on the lines that cross borders, the infrastructure lines. Then we’ll wind up with the world we want, a borderless one. Parag Khanna

New America Foundation – Social Engineers and Operatives for globalization and the end of the nation-state – funded in large part by satellite communications corporation. Makes sense.

Globalization and the Privatized Administrative State

A privatized administrative state has no loyalty to the geographic boundaries of the nation‐state the same as it has no loyalty to the people of the nation‐state.

In July of 2009, Parag Khanna gave a TED talk in Oxford, England titled: Mapping the future of countries. It’s an important presentation because he is talking about the conversion of political systems from those based on political geography (nation‐state) to political economy (economic centers). Borders are meaningless when political economy dictates policy. That’s globalization.

Khanna begins his talk by showing two maps. First the nation‐state map:

Nation-State map

Then the economic map that Khanna calls TEDistan. Khanna: In TEDistan, there are no borders, just connected spaces and unconnected spaces. Most of you probably reside in one of the 40 dots on this screen, of the many more that represent 90 percent of the world economy. (Note: the only color on the map is under the backward half moon.)

Political economy map

The following are other important quotes from the transcript of Khanna’s presentation:

This is just to give you a taste of what’s happening in this part of the world. Again, globalization Chinese style. Because globalization opens up all kinds of ways for us to undermine and change the way we think about political geography. So, the history of East Asia in fact, people don’t think about nations and borders. They think more in terms of empires and hierarchies, usually Chinese or Japanese.

Well it’s China’s turn again. So let’s look at how China is re-establishing that hierarchy in the far East. It starts with the global hubs. Remember the 40 dots on the nighttime map that show the hubs of the global economy? East Asia today has more of those global hubs than any other region in the world. Tokyo, Seoul, Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore and Sidney. These are the filters and funnels of global capital. Trillions of dollars a year are being brought into the region, so much of it being invested into China.

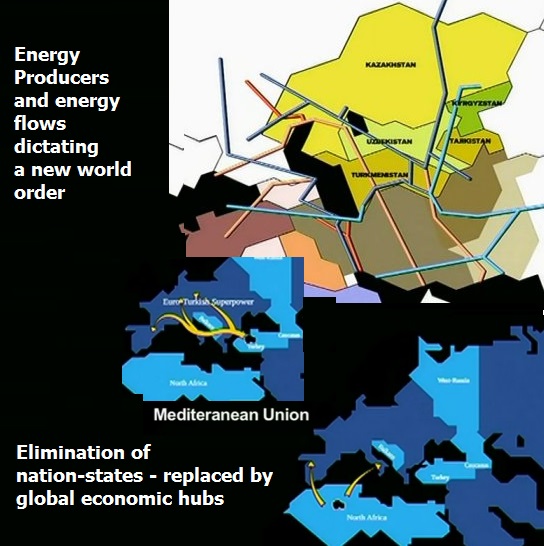

Why did he call it TEDistan? Because the world is being redefined by globalized commercial connections – the most important of which are energy connections. The connections are pipelines, electric transmission grids, railroads, highways and telecommunications – fiber optic cables for the Internet.

You know there has been a global power shift when a whelp like Parag Khanna feels secure enough to openly declare their objective is to undermine the nation-state and then to present a new order of the world – and you know that what he is talking about – is what is actually happening.

Last lines in Khanna’s presentation:

The question is how do we change those borders, and what lines do we focus on? I believe we focus on the lines that cross borders, the infrastructure lines. Then we’ll wind up with the world we want, a borderless one.

The new world leaders are the controllers of global hubs and the globalized commercial connections. Effectively, they are a breakaway civilization and they are redesigning the systems of the world to suit their own economic and political interests through the IT systems that control the flows through the critical infrastructure through which the energy and money flows.

The following is a collage of the diagrams Khanna displayed during his presentation. The point is to show who controls Europe and why and what they intend.

The second part of the strategy in the shift of global power – is to global hubs:

Lockheed Martin Corporation History

Company History

Formed in 1995 via the union of the nation’s second- and third-ranking defense contractors, Lockheed Corporation and Martin Marietta Corporation, Lockheed Martin Corporation is the world’s largest defense contractor. Lockheed Martin further broadened its lead over second ranking McDonnell Douglas with the January 1996 acquisition of Loral Corporation’s Defense Electronics and Systems Integration for $9.1 billion and $2.1 billion of assumed debt.

However, Augustine’s most dramatic move came in 1994, when Martin Marietta and Lockheed announced a “merger of equals.” It took the Federal Trade Commission several months to approve the union, which created the world’s largest defense company. While the federal government typically discouraged such massive combinations within the same business area, it regarded this consolidation in the defense industry with favor, since, according to one statement, it “boosts the industry’s efficiency and lowers costs for the government, which in turn benefits taxpayers, shareholders and employees.”

. . . The unified company was involved in a number of well-publicized projects, including the Hubble Space Telescope, Motorola’s Iridium satellite telecommunications system, the F-22 Stealth fighter, Titan and Atlas space launch vehicles, the Space Shuttle program, and the space station Freedom.

. . . Loral Chairman and CEO Bernard Schwartz held those same positions at the newly-formed Lockheed Martin subsidiary and was invited to join the latter company’s board of directors. Schwartz, Tellep, and Augustine became the first members of Lockheed Martin’s three-man office of the chairman as a result of the acquisition.

LA Times, 1996 – Lockheed Will Buy Loral Corp. for $9 Billion

Loral, based in New York, is itself the result of a flurry of recent acquisitions engineered by Bernard L. Schwartz, the company’s chairman and chief executive. Schwartz will head the new company, to be known as Loral Space & Communications, and become vice chairman of Lockheed Martin.

Loral Space & Communications Ltd.

Company History

“When we created Loral Space & Communications in 1996, we had a very specific mission in mind for the company: Capture the exciting opportunities represented by the satellite-based communications and information technologies emerging at the brink of the 21st century. Since then Loral has aggregated some of the most important assets and resources in the industry. In the process we’ve created global satellite-based networks for services like video broadcasting, data delivery and Internet access. These unique global networks, arising from and coupled with our satellite manufacturing and technology capability, advance our mission to develop and operate a seamless, global networking capability for the information age of today and tomorrow.” –Bernard L. Schwartz, chairman and CEO

Loral reaffirmed its position as the country’s fastest growing defense company through purchases of IBM’s federal systems division in 1994 and of Unisys Corp.’s defense business in 1995. Loral outbid several defense giants, Raytheon in particular, to acquire the latter for $862 million. Including these buys, Loral had acquired seven sizeable businesses in the previous six years as conglomerates sold their defense holdings in the wake of Pentagon cutbacks.

Loral and 11 other partners (including France Telecom, Daimler-Benz Aerospace, Hyundai, and AirTouch Communications) established holding company Globalstar Telecommunications and subsidiary Globalstar L.P. in order to enter the global satellite phone market. However, reported Forbes, investors were skeptical of the proposition. The sale of Loral’s defense business would help finance the development of Globalstar.

Lockheed Martin bought most of Loral–43 separate companies–in April 1996 for $9.1 billion. (A year later, Lockheed would spin off most of these businesses as L-3 Communications.)

As part of Lockheed’s purchase of Loral, Loral shareholders were issued shares in Loral Space & Communications, Ltd., a new entity encompassing Loral’s satellite business. The “new” Loral started off life with $700 million in the bank. At its helm was Loral’s old chairman, Bernard Schwartz, who viewed the satellite business as a choice growth prospect. Loral owned 51 percent of Space Systems/Loral and 34 percent of Globalstar. A 23 percent shareholding in K&F Industries, which made aircraft brakes, rounded out its portfolio.

Stock in Globalstar, the Loral-led satellite phone consortium, doubled after the Lockheed acquisition. Loral had invested $125 million for its 34 percent share; its original partners had anted up another $705 million. A 1995 initial public offering provided $200 million. Globalstar aimed to undercut its competitors by employing a simple system that accomplished switching on the ground. Inmarsat, the only global phone company at the time, charged $15,000 for a briefcase-sized phone and $4 a minute for usage fees. To gain market share quickly, Loral set up Globalstar as a wholesaler, giving the world’s existing phone monopolies a commission to offer the service. To become profitable, stated Schwartz, Globalstar needed to sign up 200,000 subscribers for $.70 a minute calls on $750 pocket-sized phones. (Motorola’s Iridium consortium was planning to charge $3 a minute for its service.)

However, Loral was not betting entirely on Globalstar. The company bought AT&T’s Skynet satellite business on March 14, 1997. The disappearance several weeks earlier of one of Skynet’s two satellites knocked the price down by $234 million to $478 million.

Also in development was the CyberStar system for broadband communications. Rather than compete directly with the cable and telephone companies in various countries, Loral planned to arrange Globalstar-style marketing agreements with them.

Due to questions of cost and availability, a number of U.S. companies contracted to have their satellites launched on Chinese rockets. One of these, a “Long March” rocket carrying a $200 million Loral satellite, failed upon launch in February 1996. After the failure, Loral and Hughes allegedly provided the Chinese with satellite launch data.

Schwartz and his counterpart at Hughes both lobbied President Clinton to relax sanctions against China; in fact, Schwartz was the Democratic Party’s largest personal contributor in 1997, according to the New York Times. Schwartz explained that the timing was a coincidence, that his contributions had gone up at the same time as his personal wealth. Schwartz had long been a staunch supporter of the Democrats, which made him a rarity among defense executives.

During the investigation, in February 1998, Clinton signed a waiver allowing Loral to launch another satellite on a Chinese rocket. Both Clinton and his predecessor, George Bush, had authorized several of these launches before. In cases like these, there was also typically pressure from the venture’s Western insurers to get at the root of the crash.

In September 1998, 12 Globalstar satellites aboard a Ukrainian rocket were destroyed in another disastrous launch in Kazakhstan. Though the company was insured, the loss pushed back deployment of the Globalstar system at least a year. One satellite that did make it into orbit was SatMex-5, a Mexican venture 49 percent owned by Loral. Loral was also operating the Telstar 6 satellite and had plans for three more. Other joint ventures included SkyBridge and Europe*Star, both with Alcatel Space Industries of France.